Psycho II (1983): A Killer Sequel

Continuing the Norman Bates story, decades later and without Hitchcock, somehow works.

Psycho II is a killer sequel, expanding a universe that already felt complete and self-contained. Hitchcock films aren’t supposed to have sequels, not least by other directors… but that’s what they did, and it’s great. A character study of Norman Bates, it surprises in how well it picks up and runs with a story told in theatres more than twenty years before.

Part of what makes it such a good sequel is a surprising degree of continuity with the original. Anthony Perkins returns, and the film is directed by Richard Franklin — an under-appreciated Australian director who made the excellent, offbeat, Hitchcockian thriller Road Games (1981), and who happened to be a massive Hitchcock fan.

Unlike the original it is shot in colour, but it follows a very classical style of editing and photography. Tom Holland, who went on to direct Fright Night (1985) and Childs Play (1988), has screenwriting credits.

On the basis of this staff report, Norman Bates is judged restored to sanity and is ordered released forthwith.

Anthony Perkins slips into character as Norman Bates, after twenty-two years, like into well-worn slippers. Similar to what was done more recently in Twin Peaks: The Return (2017), the film takes the real-world gap between movies and runs with it, using it as the length of time Bates was confined in the mental institution.

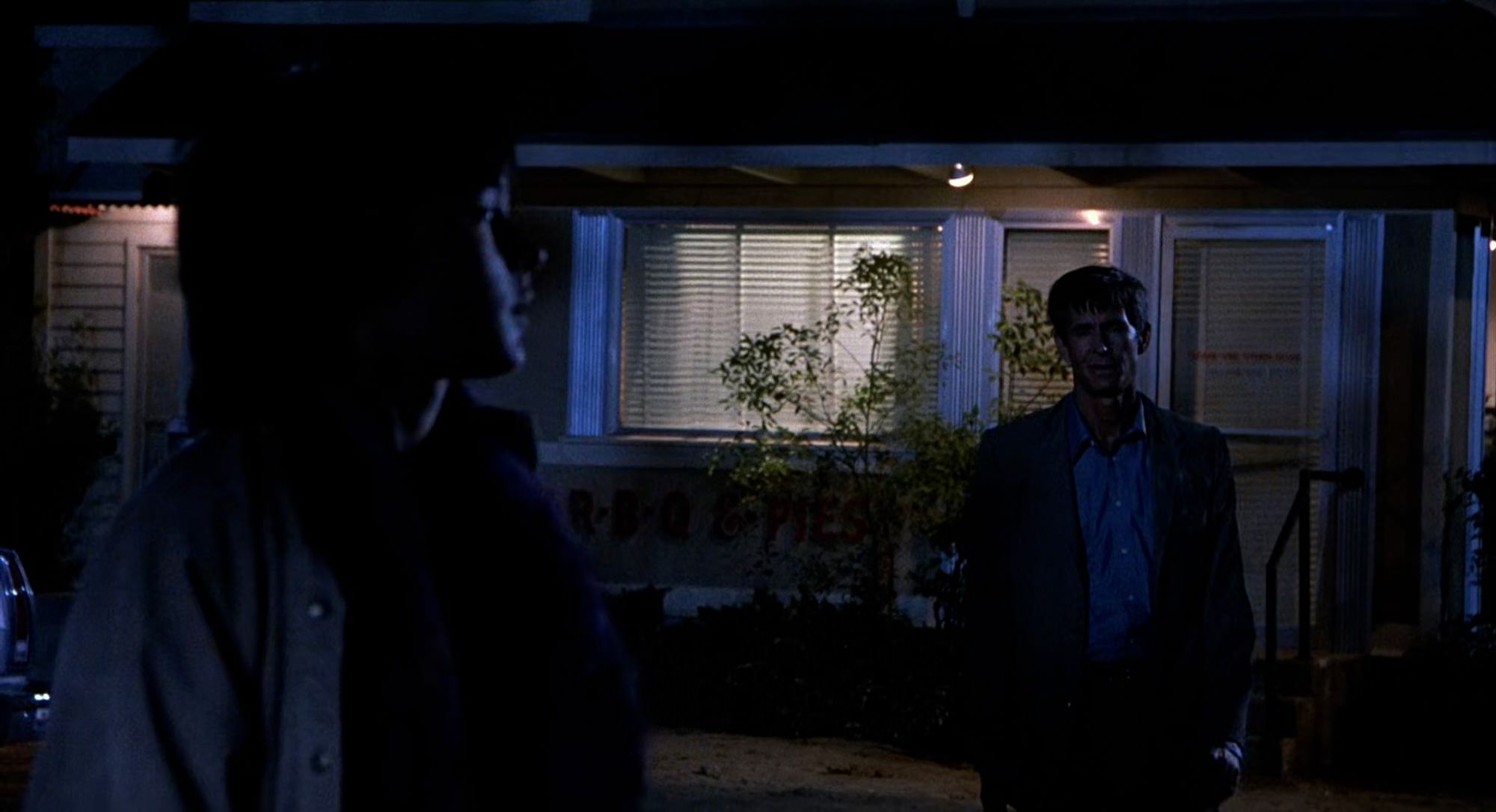

The story begins with Bates being released from the hospital after being declared legally sane and returning to his motel. There he discovers the state-appointed management has been allowing the motel rooms to be used for nefarious purposes. He finds drugs paraphernalia in one of the vacant rooms and, outraged, sacks the manager, who mentions off-handedly finding teens having sex in the basement of his house, and is up front about the seedy way the motel turns a profit.

Bates retakes control over management and makes plans to restore it to its former glory. He also takes on a shift at the local diner as cook’s helper. The town residents are willing to give him a second chance, owing to the length of time he spent locked up, and the fact he has been legally declared cured.

What kind of motel are you running here?

Perkins has an on-screen electricity. He hits false, off-beat, and creepy notes that can send shivers down your spine — sometimes with just an expertly gauged affirmation (“Absolutely!”) —, then shifts gears and shows a genuine inner turmoil and struggle in Bates as he tries to overcome his demons (“It's starting again!”).

His performance creates nerve-wracking on/off rhythms few horror films achieve, and that show how significantly he contributed to the tension of the original. Hitchcock can't take all the credit.

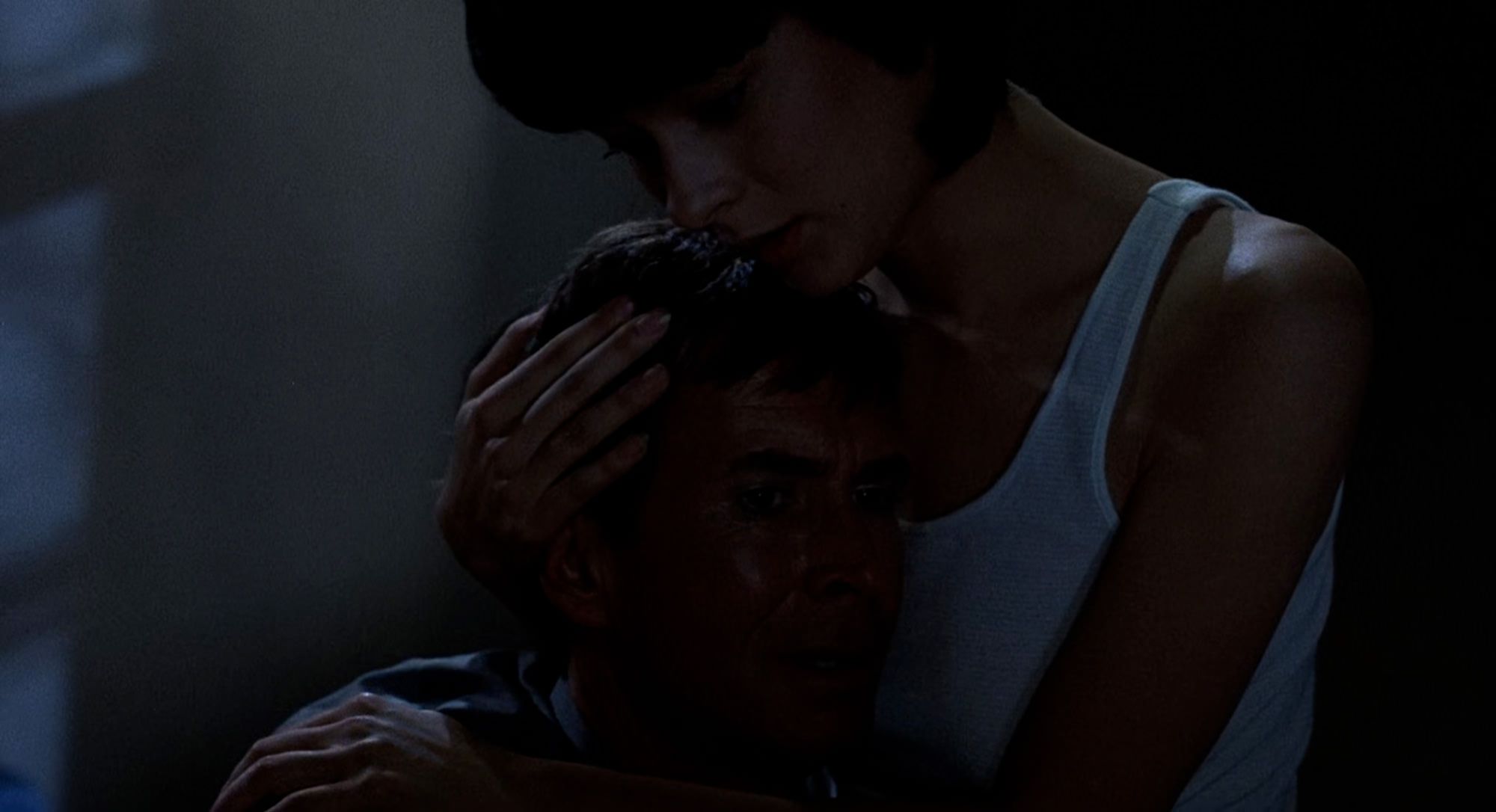

The plot centers around the relationship between Bates and Mary, a young woman who works with Norman at the local diner. Norman stumbles on Mary in distress, abruptly dumped by her boyfriend and in need of a place to stay. He kindly offers her a room at the Bates Motel “FOC” (Free Of Charge), which she reluctantly accepts.

Bates appears to see Mary as a shelter from the storm of the hostilities of the outside world, a healer of his psychic wounds, and as prey — all at once. In moments he is running a con on her, in others he wants to help her, and in others still he is seeking help from her. Sometimes he is doing all three at once.

This predator/prey charade is reversible, applying to Mary and her motives towards Norman, too. She seems to be running her own con on him, but also in moments seeing something good or innocent in him, and feeling genuine trust towards him. In moments she resolves to protect him. Bates welcomes her sympathy, perhaps glibly, or perhaps because he is simply in need of it.

This confusion of roles makes the dynamic between the two characters dramatically fruitful. The uncertainty about where each stands in relation to the other, and what their true interests and intentions are, keeps the viewer off balance and creates tension.

At heart the film is a deeply sympathetic study of Norman Bates. It strives to show the viewer his struggle to maintain sanity and fight his murderous impulses and the delusions. As such, at times it functions as a touching portrait of a man at battle with his demons. More than the original, it makes the viewer walk in Norman’s shoes.

Mary, I'm becoming confused again, aren't I?

Bates is at once horribly twisted, and an innocent soul at the mercy of deep-seated defects in his psyche, causing murderous delusions that could reoccur if sufficiently provoked. And there is no doubt he is surrounded by provocateurs, both real and imagined. Also, his abrasive personality means he creates enemies from almost the moment he is released.

The story considers how society mistreats those suffering from psychosis, and how being mistreated feeds into and affects their behaviour. It asks whether otherwise functional individuals, who are fragile, can be pushed over the edge by manipulative agents pulling their strings and working against their best interests. It also considers if such manipulation can be justified.

Just don't let them take me back to the institution, all right?

A theme of crime and punishment runs through the narrative. Has Bates been cured? Should he be released? If he is cured, should society give him a second chance? Are the police taking fresh accusations about him seriously enough? Is the justice system set up to protect the criminal and punish the victim? These questions swirl in the plot.

Where the film comes down on the issues it explores is left ambiguous, and can be read in more than one way. It is a subtle, well-written script that refuses either to clearly side with Bates, or to simply define him as evil.

The writing channels something of a literary style of screenwriting common at the time of the 1960 original. It is carefully written with multiple viewpoints, but unapologetic in showing fringe viewpoints or critiquing mainstream thought. It writes earnestly from both sides of the coin.

When I was little, I had a fight with my mother, so I put some poison in her tea, you know. But I'm all right now.

This is a sequel that pays attention to fans of the original. It recognises the sympathy fans felt towards Bates at the time, and makes that its central theme. There is a feedback loop where the audience of the first film helps shape the second — which could be either good or bad. Here, it is clearly good: the character of Norman Bates had further depths to be explored, and delving into his psyche reveals fertile dramatic ground.

Psycho II is not a better film than the original. It performs a role in service to it, enhancing the original and increasing its intrigue — expanding the universe Hitchcock created, and the mythology of Norman Bates, and giving fans something to sink their teeth into. The fact it was able to do all that without fucking things up? Makes it pretty damn amazing.

James Lanternman writes movie reviews, essays, and moonlit thoughts. You can reach him at [email protected].

Previously… Some Days